Cittern music transcribed for the ukulele

I recently treated myself to a copy of

Sprightly and Cheerful Music by John M Ward (Pub: Lute Society, 1983). A most erudite publication, covering music in MS and print for the cittern and gittern/guitar in 16th and 17th-century England.

My main aim was to mine it for music to play, preferably obscure.

There is a lot of uncertainty about what was a gittern and what a guitar. Ward implies that a gittern was a cittern tuned like a guitar. I get the impression that he preferred the cittern.

Ever curious, I decided to transcribe a cittern piece, and see how it played on the ukulele (and Renaissance guitar).

|

| Jan Vermeer: Lady with a letter (and cittern) |

I have never seen a cittern. It differed from the guitar in having a teardrop-shaped body, and paired wire strings that went over a free bridge, and were attached to the base of the body. It had a longer existence than the 4-course guitar (which was replaced in the 1600s by the 5-course Baroque guitar) and carried on into the 18th century.

In the Tudor period they were tuned in a number of ways, which must have been very confusing. The commonest was:

1st E4

2nd D4

3rd G3

4th B3

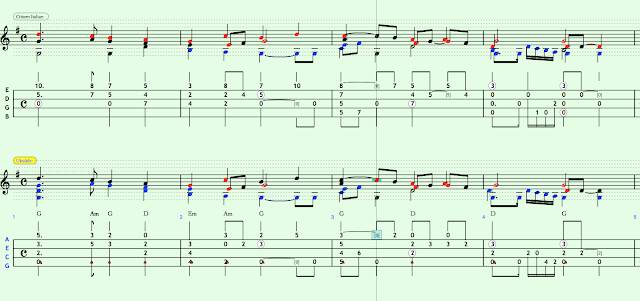

So, it was re-entrant, and difficult to get my head around. Fortunately, the music setting software I use (TablEdit) let me create a virtual cittern, and enter the tablature directly from the transcription in Ward, pp 52 – 53). This gave me both tabs and mensural notation. It was then possible to intabulate for the Ukulele from the notation. Both instruments being tuned in G (at least notionally), this was not too difficult. Below you can see the first 4 bars of Ward's transcription ...

|

Ward 1983, p. 52.

The fingering positions: a = nut (open), b = fret 1, c = 2 ... y = i = 8, and so on. |

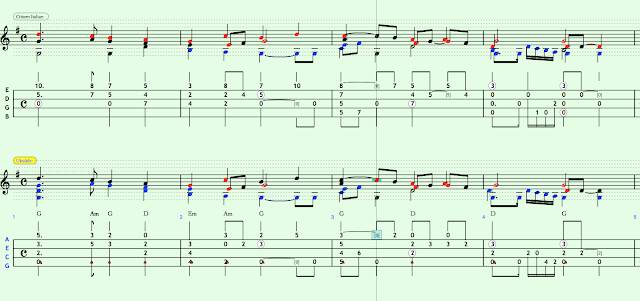

... and the same bars in the TablEdit editing screen ...

|

| From the top: Cittern notation and tabs, low-G ukulele notation and tabs |

Cydippe (Ancient Greek: Κυδίππη, Kudíppē) could have been one of a number of Greeks in classical times, including one of the Naiads (water nymphs). I don't know to which one this piece was dedicated.

The arrangement fits pretty well on the uke, despite the weird tuning of the cittern. I have tried to keep as close as possible to the original, although some chords might be easier on the ukulele if other inversions are used.

I have changed the first chord in bar 11 to D major (sus 2) as the original chord sounds horrible. It then forms a bridge between the previous chord (A) and the next (G). The original discordant version is appended to the arrangement, for your delectation.

There are 3 strains of 8 bars (4 + 4), set in G, D and G. The harmonies can change rapidly, and the whole piece feels that it is an elaboration of grounds (block chords). In Ward’s book, many of the cittern pieces given as tablatures are obviously strums with single-string work, played using a quill as a plectrum. I chose this piece as it seems more suitable to finger-style.

This being the blog of someone learning as he goes along, I shamelessly follow Ward’s scholarship, and append a strummed consort version of the same name (almost) by John Farmer, which Ward transcribed from a publication (Rosseter 1609). Bar 17 in the published transcription contains enough notes for 2 bars, so I have split it, which also brings the total neatly up to 24 bars. The harmonic structure is broadly similar to that in more elaborate version (the three sections set in G, D and G), but the whole is much simpler and practically all chords are in nut position.

Available to download free in the following formats:

- pdf

- TablEdit (including both cittern and ukulele scores)

- MIDI (Basic; watch out for the horrible chord between pieces.)

Have fun!